Careless Consuls and Unbearable Boats

In 1940 the British consuls up and down the Riviera were in rather a quandary: As the military situation deteriorated they were unsure what to do with their remaining expatriates as, it seems, was the British government. The blackout had ceased to be firmly enforced in the south and civilian traffic was allowed to take freely to the coastal roads. The British authorities had done nothing to discourage their subjects from visiting or returning to the region in spite of the increasing menace from Italy. From May onwards, when the situation in the north became more dangerous, British refugees from Italy, Belgium and northern France had joined others flocking to the south. F.C. Stone, an employee of the British Consulate in Monaco, a neutral principality, recorded in a long memorandum to Anthony Eden at the Foreign Office, ‘Constantly augmented by the dwellers of the towns and villages, soon over two million people were crawling at a snail’s pace along the roads of France, engulfing on the way military convoys and fugitives from the front. The columns of refugees were bombed and machine- gunned by the Luftwaffe and they buried their dead by the roadside.’

During the meeting of the consular staff it became clear that Major Dodds had been instructed by the British Embassy to leave his post and escort the Duke and Duchess of Windsor to a Royal Navy destroyer and on to safety in Spain. Later, back in Britain, Dodds would declare that the only way the south of France could regain purpose and honour would be for the Germans to occupy it completely, presumably then the majority (if not all) of the population would know who their real enemy was – and that it was not other Frenchmen. He had to wait a while before his theory could be put to the test.

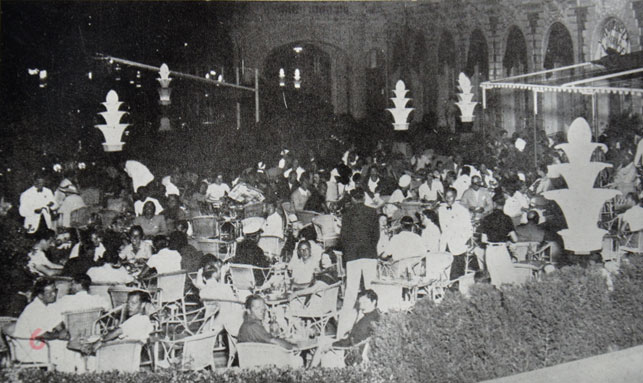

But hopes rose, for on 17 July two British cargo ships, the Saltersgate and the Ashcrest, were suddenly made available. The advice to leave now became an order to evacuate. If this chance was not taken, the British government would accept no responsibility for the fate of those who remained. Everyone was to be at the Cannes Customs House early on the following day. What everyone did not know was that the ships were two colliers – iron-decked, grimy coal boats from Liverpool, equipped for a small crew and now asked to take 1,000 refugees and not equipped for those. The evening before the embarkation, the Carlton Hotel on the Croisette was brilliantly lit and crowded. In his book ‘Strictly Personal’ Somerset Maugham, staying the night there before joining the exodus next day found, ‘They were in evening clothes, some of them a trifle the worse for liquor, and there was about them an air of hectic, hysterical gaiety, which was sinister.’

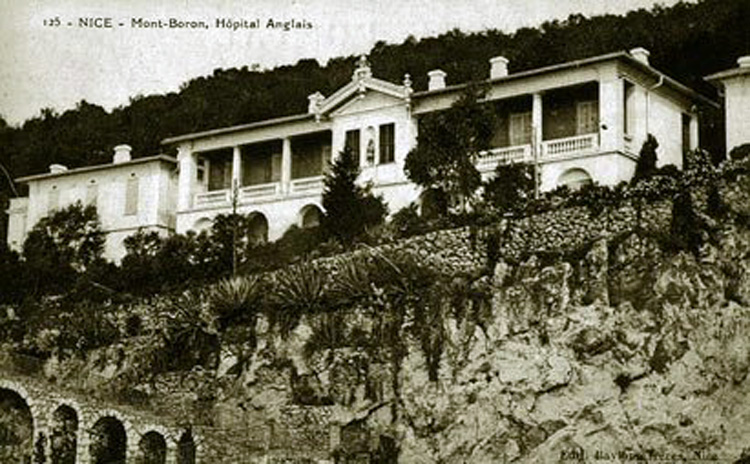

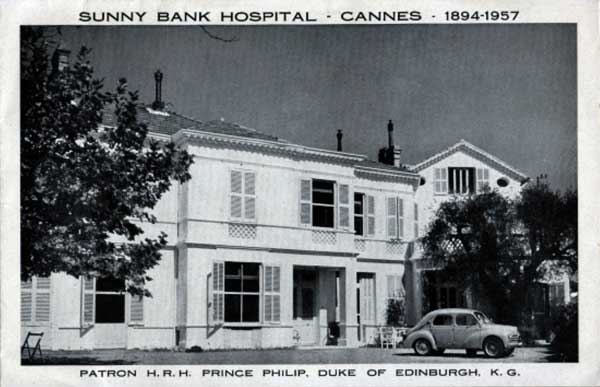

In contrast, the scene at the Customs House on the morning of 18 July was despondent. Those who could be contacted, and who had chosen to leave on the ships, were gathered together in the early morning heat. Each person was allowed one suitcase and told to take a blanket and some food. Although some were rich society people who had hung on until the last minute, the majority were older and less well-heeled, retired army officers and colonial civil servants, governesses and employees of great villas and various businesses. Among them were a few just-recovered patients from the Anglo-American Sunny Bank Hospital in Cannes, who had decided to chance the voyage. The other British hospital, the Queen Victoria at Nice, had brought their remaining patients to Cannes, mostly on stretchers, for the hospital had closed its doors that morning, being on the Italian side of the Var River. It was quickly realised it would be impossible for anyone who was ill to embark on such ships, so they were taken up the hill to Sunny Bank Hospital which the matron, Margaret Williams, was determined to keep open and which was about to begin five long, lean and anxious years.

Cars were sold for a song or abandoned on the quayside and Consul Stone of Monaco recorded, ‘A large crowd of French people had come to see this melancholy sight and many were openly affected by the departure of these British whom they had always regarded not only as their patrons but also, in many instances, as their friends.’ On the two ships, of which the largest had quarters for a crew of only thirty-eight men, 1,300 were eventually crammed on board, the iron decks burning from a day at rest in the Mediterranean sun. As Somerset Maugham, sailing on the Saltersgate wrote, ‘One lady, when she came on board, told an officer that of course she wanted to go first class and another called the steward (there was only one) and asked him to show her where the games deck was. “It’s all over the ship, madam,” he replied’. What followed was one of the worst journeys the passengers would ever experience, before the boats arrived safely back in Britain.

Rumours circulated about the swift departure of the staff of the various British consular offices. Major Dodds, ordered to escort the Windsors, had left quickly, returning only in August. He would be later be transferred to Marseilles as an attached advisor to the American Consul General. According to Consul Stone of Monaco, Dodds now ‘regretted his rapid departure’. The British Consul General of that Principality left his office to the care of Stone, without taking leave of the Prince of Monaco or the Monégasque government, which action was not looked upon favourably. The Consul at Cannes announced that he would stay – and was gone by the following day. As Stone reported, there were those who felt the consular officers and their staff should have considered their duty required them ‘to share the fate of the people under their protection’, and that in this they had been less than valiant. The staff of the Cannes office were particularly criticised.

But it was the Italians who first invaded and, for the moment, things were not as bad as anticipated.

© Copyright: Maureen Emerson 2021

From: Riviera Dreaming – Love and War on the Côte d’Azur

Sources:

- Consul Stone’s account. The National Archives, Kew.

- Strictly Personal. Somerset Maugham.

- The archives of the Sunny Bank Hospital.