The British Riviera

Eric Cipriani Dunstan

‘The Man with the Golden Voice’

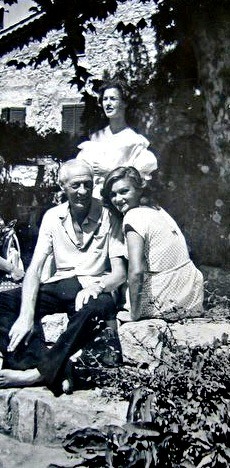

THE MILL HOUSE IN THE HILLS 1938

One January day in Mexico Eric Cipriani Dunstan, ex-BBC announcer, ‘The Man With the Golden Voice’, stood clutching a bunch of wild flowers and watched with horror as the car containing his wife of almost three months careered down a steep incline before bumping to a stop at the bottom. It was 1938 and Flora Stifel, from West Virginia, was in the car with her maid. Their chauffeur, who had not engaged the hand brake properly, remained standing among the wild flowers with Dunstan. The incline down which the car slid, near the town of Cuernavaca in Mexico, was known as The Death Drop.

In 1935 Dunstan had asked the American architect, Barry Dierks, to restore an old mill house in the hills almost 13 kilomers above Cannes. Although the house itself was tumbling down it was set in a virtual Garden of Eden. Twenty hectares of water meadows were flanked by hills of cistus, cork oaks, mimosa and vines. On red soil and limestone, wild flowers such as marsh orchids, Canterbury bells and anemones flourished. The property was flanked by the fast flowing six meter wide river, clean and sparkling in the sunshine and replenished by its own small cascade. Its sluices would ensure that Dunstan was able to create wide expanses of lawn, evoking an English garden. One wonders whether his earnings as commentator and journalist would have permitted him to commission the restoration of the old mill to the high specifications of the elegant and comfortable house it became once Barry and Eric Sawyer had eventually finished their work. But by then he had met Flora.

Dunstan owed his exotic middle name to the composer Philip Cipriani Potter. In 1891 she married Malcolm Rowley Dunstan, who would have a distinguished career as director first of the Midland Dairy Institute and then of Wye Agricultural College in Kent. Their son Eric was born in 1894 at Hamilton Drive in the shadow of Nottingham Castle. A tiny baby he would grow to a slim one meter 90. Eric would have no children but his two sisters, Joan and Hester, ensured the continuation of the Dunstan line.

Sent to Radley College in Oxfordshire which, at that time his prep school considered the ‘Home for Lost Dogs’, Dunstan, in his engaging and typewritten autobiography writes that his years there were uneventful, ‘at games I was a wreck’. His final report on leaving said he had, ‘a positive genius – for doing the minimum of work and escaping detection’. But he had a good voice, good enough to gain a singing scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford where, in 1912, he became an Academical Clerk, singing Bass with a grant of £95 a year, having beaten fourteen other candidates to the post. An Academical Clerk became a member of the College choir but was also expected to attend lectures, tutorials and graduate like other students.

So one damp October evening in 1912, searching for his rooms he found his way through ‘the dim-lit foggy Cloisters to my door’. Here his path was partially blocked by packing cases containing glass and silver ware – Edward, Prince of Wales, was moving into the rooms next door. Dunstan and the Prince would become casual friends at Magdalen.

When war was declared in 1914 Dunstan, like so many other eager young men, joined up two days after the declaration of hostilities, leaving his studies abruptly. His first posting was as 2nd Lieutenant with Kitchener’s 2nd New Army. After training he spent six months on the Italian Front and through the subsequent retreat. But it was not long before he was writing to the President of the College ‘Magdalen seems like a vivid dream’, asking that his place be kept open in the event of his return. Back in England he transferred to the 7th Service Battalion East Kent Regiment, known as The Buffs, and was sent back to France with the rank of Captain. Posted again to the Front, he went on to run a Bombing School as Brigade Bombing Officer – ‘a perilous experience, but I was lucky and so were my pupils’. Tuberculosis put an end to his time in the army and probably saved his life. In 1916 he escaped the 1st July battle of the Somme where his battalion lost 22 officers. Accepted back into Magdalen, he graduated finally in 1917. Now, cured of tuberculosis, he had to find a job.

Meanwhile Dunstan began the first stages of his long career. Beginning as a lowly assistant to the British consul at Seville he was appointed a Sub-Commissioner in the Red Cross, on the Italian Front. In 1917 he became involved in the Austrian attack on Caporetto in which the Red Cross would lose 80 of their 130 ambulances. Returning to London he jumped at the casual offer of assistant to the Governorship of the Fiji Islands, setting sail for Australia on a Union Castle freighter transporting 300 Australian soldiers’ English wives going to join their husbands – an interesting journey during which six babies were born. From there it took three months to travel by sea to Suva, the capital of Fiji. He was entranced by Fiji ‘our pleasures are Arcadian’.

But feeling he must at last try and earn some proper money he eventually returned to London where he took a job in the Basement Department of Selfridges on Oxford Street, working his way up rapidly to become private secretary to Gordon Selfridge. An enormously successful and innovative retailer, Selfridges’s one weakness was women, the more expensive and extravagant the better. His long suffering wife had died in the influenza epidemic of 1918 but his formidable mother kept him more or less on the straight and narrow until her death in 1924, thus avoiding the worst of the scandals which would later beset him. Dunstan lived with Selfridge and his four children in his rented Landsdowne House on Berkeley Square. He became an excellent and supportive private secretary, staying with the store for six years during a period when Selfridges ruled the roost among stores in London. Flamboyant displays and promotions constantly drew crowds to the windows and into the store.

Feeling himself ‘always lucky’, Dunstan then met a friend who worked in the BBC and so began an eventful life as an announcer, journalist and commentator. He made the point that announcing in those far off days was a novelty which gave the person concerned a mysterious glamour, though requiring ‘no more than a clear speaking voice and a modicum of common sense’. A formidable presence in the BBC at that time was the complicated and dictatorial Director General, John Reith. Although Dunstan compliments him for having fought for the integrity and dignity of the Corporation, his eventual clash with Reith would make BBC history. But in 1926 he was sent to India to set up the poorly funded Indian Broadcasting Company. From Dunstan’s correspondence of that time it is clear how hard he worked to make the Broadcasting Company succeed and how much and how often he tried to encourage investment, but in vain. After three years he resigned, mortified at the failure of what he felt had been an inspired idea. The company went bankrupt, later becoming the Indian State Broadcasting Company, and Dunstan returned again to England. Back at the BBC once more and now a Senior Announcer, he had a rather spectacular falling out with John Reith. This was over the way in which Reith was announcing the General Election results of 1929. Listeners began to telephone the company to complain about Reith’s unclear and too-fast style. When Dunstan undertook to inform him of this a clash of well-developed egos resulted in him being out of a job once more.

He was out of work for all of several hours. That afternoon he received a telephone call inviting him to visit the Editor of The Star newspaper, run by the Quaker Cadbury family. He became one of their journalists and the first radio critic on a daily newspaper. Launched in 1888 the Star would always be a liberal paper ‘championing the cause of the underprivileged and highlighting the needs of working class families’. Something new for Dunstan, but he had a happy, well paid, relationship with his new bosses, a relationship which would last for eight years. He deemed the Cadburys and their associates ‘the best employers in Fleet Street’ and was gratified to see ‘Read Eric Dunstan in The Star’ twinkling in lights in Leicester Square. Lucky again.

British Movietone News was launched in 1929 and became the first sound newsreel in Britain. The parent company was Fox Movietone News in America and British Movietone went into competition with other newsreels, such as Pathé. Dunstan joined them soon after the launch and so began to present once again. He was now a commentator, providing commentaries on events, national and international, rather than an announcer relaying the news of the day. Known as ‘the man with the golden voice’ to present day ears his delivery seems clipped, even staccato, but that was of his time and his voice is very clear. He would say this was ‘something between a butler’s and a bishop’s’ which meant he was in demand for solemn occasions such as important funerals and international events. He commentated on the events of the Abyssinian-Italian war, the Silver Jubilee of King George V in 1935 (which showed the first colour newsreel) and the funeral of the King in the following year. This was followed by the Coronation of King George VI, the father of the present Queen, in May 1937. Now famous, admired and well paid, he was settled and happy.

Dunstan would take his holidays on the Mediterranean and one year, planning to visit Morocco, he found himself stranded in Marseille – his boat having been shipwrecked. Instead he took a plane to Tunis and from there to what was then the small town of Hammamet, 76 kilometers south of Tunis, and built on the Gulf which bears its name. He found a simply furnished white room and felt it was all perfect. And it was here he met Flora. Flora Stifel was from West Virginia, and what she lacked in good looks she made up for in extravagance. She had married previously an aristocratic Romanian with light blue, slightly unnerving eyes and the profile of a Greek statue. Karl Georges Sebastian was then 33 and Flora 52. This marriage of convenience would produce one of the most stunning private houses in North Africa. Their marriage was, for a while, a fruitful partnership. Sebastian was homosexual – a fact which seemed to suit Flora very well. Social life was far easier with a husband in tow. The third person in their marriage was Sebastian’s enduring friend, the American artist Porter Woodruff, responsible for many of the covers of Vogue magazine of that time.

The house created by Flora and Sebastian on the Bay of Hammamet near Tunis was designed by Sebastian and built by an Italian builder. It had all the elements of a perfect Moorish building. Flat-roofed, sharp edged and sparkling white, it contained arches, arcades, courtyards, large cool rooms with wide groined ceilings, terraces, studded doors – all the romance of North Africa was there. They called it Dar Sebastian. It is now the Hammammet Cultural Centre. Many artists, actors and celebrities visited Hammamet during the 1920s and 1930s, lured by its beauty, simplicity and those expatriates who had built elegant houses on its shores. Among these visitors were Ernest and Wallis Simpson. In 1932 the Simpsons were in straitened circumstances and Sebastian, wishing to show them his Hammamet home, sent them two return tickets from London. The trip was to be in March and would include a journey to the edge of the desert. Wallis wrote to her aunt, Mrs Buchanan Merryman, that she would buy only ‘one light coloured flannel suit for the trip, which could be used here [in England] in the country afterwards’. By the time Flora and Georges Sebastian visited her in London in 1934 Wallis was worrying less about clothes. Her affair with Edward, Prince of Wales, was well under way and she had ‘bought a coat and dress with the $200 the Prince gave me … along with some leopard skins’.

Eric Dunstan returned to Hammamet several times but was not at ease with the cosmopolitan, pleasure-seeking set who built their attractive houses in the bay:

‘As there so often is with those exquisite beauty spots which attract intelligent, idle people … the intimate friend of one day is the bitter enemy of the next’. I could never be sure from one year to another who would be friends with whom – which was a pity’.

But he valued the country for its culture and Roman and Phoenician history, evident in its many, then scarcely explored, ruins. He always appreciated the people of the places in which he travelled saying: ‘When people say to me “I loathe the French or the Italians or the Egyptians or the Americans” I know that person has mostly himself to blame. Bad manners breed, and vice versa’. One possible enemy was Georges Sebastian, for in January 1936 Flora divorced Georges in the United States, presumably taking her fortune with her, and by September 1937 had married Dunstan, her friend from Hammamet.

It was a short-lived marriage, three months later Flora died in a tragic accident in Mexico. Her death left Dunstan a rich man.

Later that year Dunstan returned to Provence and began work on the shell of the old mill with Barry Dierks and Eric Sawyer whom he counted among his friends for, ‘rare is the architect like Barry Dierks who combines his own taste with a capacity to satisfy the personal taste of his client’. With no lack of funds, building work moved quickly in those days and by Christmas of 1938 the Moulin had its house-warming party. By then Wallis Simpson was married to the now Duke of Windsor and had become his Duchess. The couple had rented the Château de la Croë on the Cap d’Antibes and entered into the confined social life of the Riviera.

Set in its idyllic valley the house, built within the old walls of the mill, was large and ancient. Outside it had the air of a traditional French country house, ochre-coloured and Roman-tile roofed. Only the large, many paned windows differentiated it from a typical Provençal mas, or farmhouse. The simple entrance door was set in a rustic porch behind a rough stone arch, the whole having a very campagnard air. Barry seemed to be always effortlessly in tune with each of his many different commissions. The wide sitting room, both elegant and welcoming, had the usual large stone fireplace to guard against damp, Provençal winter nights. No Moorish arches here, rather a set of white regularly spaced painted beams in a low ceiling. The whole house was comfortable and welcoming. Virtually the only nod to modernism was the striking narrow stone staircase, flanked by solid banisters rendered white. In contrast, the slender supporting pillars were composed of narrow red bricks, this feature being echoed in the large pergola on one of the terraces behind the house.

As far as garden design was concerned, the land was a blank canvas. Eric Sawyer, as designer, used the water in many ways, gushing out of the mouths of fauns and satyrs, in shady pools and under bridges and, in a lower part of the garden, a round swimming pool with a pool house echoing the traditional design of the main house above. A rough, arched stone bridge led to the upper part of the garden and the cascade above the river meant that one always heard the gentle sound of falling water.

Idyllic it all was – for 18 months before, as Dunstan said; ‘that lunatic bastard of a “house-painter” set the world in flames’.

Abridged from: Riviera Dreaming

Copyright © Maureen Emerson 2019

Listen to a short audio clip of Eric Dunstan’s ‘golden’ voice here

Listen to a longer video clip of Eric Dunstan paying tribute to the late of Sir Austen Chamberlain here