John Fortescue

Author, Librarian and Archivist at the Royal Library,

Historian of the British Army

In 1911, a young actress called Winifred Beech was taken by friends to a tea party at the modern, red brick home of the writer Thomas Hardy in Dorset. It would, for her, turn out to be an occasion of great significance. But not because of the brief encounter with the venerable author. Gazing across a crowded garden she saw, sitting by himself, the man she had always known she would marry. Enduringly romantic, she felt that every detail was as she had always imagined it, even down to his name ‘John’ and: ‘That arrogant pose of the small head on its long neck; that high brow, that clean-cut sensitive face … that curiously beautiful mouth, that air of bored, impatient superiority’.

Born in Madeira in 1859, John Fortescue was the fifth son and ninth child of the fourteen children of Hugh, third Earl Fortescue – and therefore without fortune. The family home was Castle Hill near Barnstaple in North Devon and it was here John developed a passion for every aspect of country life. The house stood on a hillside, between the moors of Exmoor and the sea, backed by tall beeches which swayed and moaned in the winds which swept in from the Atlantic. The trees were colonised by rooks and, as an old man, he would write from far away: ‘The noise of their cawing is now constant in my deaf ears’.

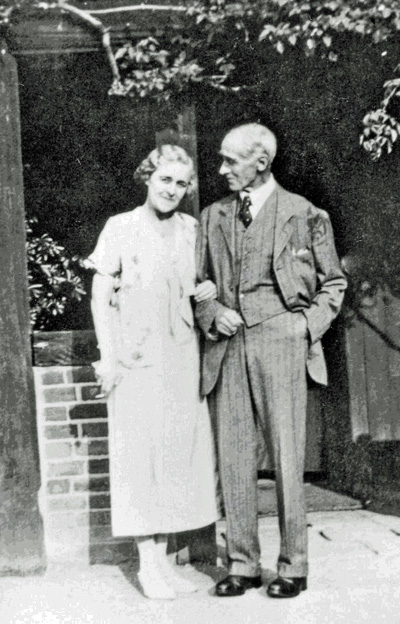

Right – Sir John and Lady Winifred Fortescue at Spilshill Court, Kent in September 1933 – possibly the last photo taken of Sir John beofre his death in Cannes later that month

Educated at Harrow, John was a delicate child with bad eyesight, which meant he found it hard to keep up with his strapping older brothers and because of this and the expense of following two of these siblings into the army, a longed-for military career was denied to him. Leaving Cambridge without the intended law degree and rather at a loss, he went for two years as private secretary to the Governor of the Windward Islands, before returning to Britain in 1882 to complete his law degree. He then obtained a post as private secretary to the governor of New Zealand. Having been denied active duty in the Army, now he began to write its history, which eventually led to a commission by the publishers Macmillan to produce the official History of the British Army. The task, embellished with elaborate campaign maps, would take him thirty-six years.

Returning to England from New Zealand, John was living on slender means in spartan rooms in London’s Brook Street, when in 1905 King Edward VII offered him the post of King’s Librarian and Archivist at Windsor Castle. It was the perfect job. Leaving the diplomatic service, with lodgings in the Round Tower at the castle and a free hand to create order from the chaos of years, while working with some of the most priceless items of history, he was completely happy. Most importantly, the post also enabled him to continue his work on the British Army. Of a retiring nature, John was nevertheless expected to attend official banquets. As a gentleman of the Household he would don the required blue swallow-tailed coat with scarlet collar and cuffs, white waistcoat, black knee-breeches, black silk stockings and pumps – the Windsor uniform. Of one of these occasions he would write: ‘The guests, of course, were all of them in uniform, the effect of which was too often spoiled by the glaring scarlet which belongs, and for nearly three centuries has belonged, to the British Army’.

When Edward VII died, King George V and Queen Mary asked him to remain in the position and he settled down at Windsor for almost twenty-five years, eventually being given rooms in Edward III’s gatehouse. In his personal habits John was so fastidious he changed every item of clothing completely twice a day and, at one stage, owned ninety-six vests bought for the voyage, with the King and Queen, to the Coronation Durbar in India in 1911.

An expert on book-binding, he began the process of designing bindings for works that had scarcely seen the light of day since their production. While sorting archival material, cataloging and purchasing historical works for the Royal Collection, he found time to continue work on his History and also during these years edited the correspondence of George III. He had already published the History of the 17th Lancers and The County Lieutenancies and the Army, as well as numerous articles for newspapers and journals. For light relief he wrote several books for children, the most famous being The Story of a Red Deer which told of the respect and reverence felt by a hunter towards an animal he was dedicated to stalking to its death.

But there was the odd mistake too. The greater part of a legacy of priceless volumes of 17th century drawings of fruit and flowers by the Italian Cassiano dal Pozzo had found its way into the Royal Library. John, pronouncing these volumes to be ‘unimportant’ sold fifteen of them to London dealers after the Great War. They were consequently broken up and the drawings dispersed. It was not until the 1950’s that their significance was realised and it was Anthony Blunt, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures and spy for the Soviet Union, who set about tracking down those of the drawings that had ended up in private hands.

So in 1911 when John Fortescue drew Winifred Beech away from the other guests to sit with him on a bench at the end of a leafy arbour her future was sealed, although nothing was said. But the romance would not be easy. John was twenty-eight years her senior and worried about the difference in age. If, and when, he announced their engagement he would have to inform both his Fortescue family (who would never really accept Winifred) and the Royal Family (who were eventually far more inclined to do so) of her profession as an actress.

When, three years later at the outbreak of war, they did at last get married it was a muted, hurried affair held in a side chapel of Holy Trinity in Sloane Street, London, with John slinking in by a side door. He had wanted ‘dispatch’. The service was over in seven and a half minutes with eleven people present. Only the small reception given by Consuelo, Duchess of Marlborough née Vanderbilt, Winifred’s loyal ‘fairy godmother’, leavened the proceedings.

Married life in London was not what Winifred had expected. Obliged at first to live by herself during the week in the little house they had taken in Brompton Square while John was in attendance at Windsor, she felt very alone. But after what may also have been a period of acclimatising as far as John was concerned, the apartment in the gatehouse at the castle was extended to accommodate a married couple. The King and Queen Mary visited them there, Winifred being greeted graciously and allowed to spend a little more time at Windsor. It was the outbreak of the Great War that allowed her to live more permanently in the relative safety of the castle, away from the threat of bombs over London.

In 1916, looking for a permanent base in London, the couple found and rented Admiral’s House in The Grove in Hampstead and, from then on, never lived apart for any length of time. Happy, and proud of his new home, John travelled to and from the castle library at Windsor while, in every spare moment, continuing to write his History of the British Army. But post-war taxation soon began to cause the money problems which would, from then on, never loosen their grip and he had to face the prospect that now he may not be able to afford the luxury of spending so many hours of low-paid work on the rest of his History. In the preface to volume nine he explained that this might be the last in the series. But Winifred resolved that he must, at all costs, carry on and that she would be the one to enable him to do so. She set to and founded ‘Cintra’, an interior decorating service, which developed into a successful couture business.

They were both working hard at their respective projects when an event happened which would shake their relatively calm world. In 1922 Winifred was invited to the United States to stage Cintra fashion shows at the Plaza Hotel in New York in aid of the ‘Soldiers and Sailors of America’. While there, John was invited to give an Armistice Day lecture to the cadets at the West Point Military Academy near New York. But on the morning of the lecture the New York Times published an article citing passages from one of John’s books, formed from a series of lectures of 1911, British Statesmen of the Great War. In this, frequently outspoken, he had accused the United States of engaging in ‘foul play’ and ‘prearranged trickery or violence’ in any form of competition. The fact that he was writing about the war of 1793-1814 rather than that of 1914-1918, helped him not at all and the Secretary of State of the time ordered the lecture cancelled. The resulting bad publicity affected the sales of Winifred’s Cintra gowns, of which so much had been hoped, and they returned soberly to England.

Left – John & Winifred Fortescue arriving in New York by liner in 1922

Rallying, a second floor apartment was found for the business at 28 Sackville Street near Piccadilly and the new salon became an immediate success. For one of her fashion shows John composed a seven verse poem entitled ‘Cintra at Olympus’. It tells of a reporter sent to Mount Olympus ‘on a special aeroplane’ to interview the goddesses for their views on fashion. One of the verses runs:

‘Then next came smiling Venus: “When I rose up from the sea No bathing dress had been supplied for pretty little me, But Vulcan didn’t mind it; and a certain God of War Said: “Clothing, Venus! Nonsense! You look better as you are.” And – well you know the scandal; it has reached your earthly flats, For Olympus hums with gossip, and all goddesses are cats! Still, I think the undraped business has been overdone of late, So I’m off to Cintra, Sackville Street, at Number Twenty-Eight.’

In spite of John’s way with words and Cintra’s popularity, costs were high and the books could not be made to balance, a situation aggravated by the occasional non-payment of bills. It seems Wallis Simpson was one who didn’t honour her account. Recurrent ill health, to which she was prone, now forced Winifred to close down the business and she embarked on a new career – that of author. It was her humourous and perceptive articles for national newspapers and magazines which would, from now on, help to support them financially.

At Windsor, one Spring day in 1926 John Fortescue, poised for retirement, was summoned in his dusty walking clothes and, with a sword borrowed from an officer on guard, was knighted by King George V. Now a K.C.V.0. (Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order) he was bidden to dine with the King that evening, without the presence of Winifred, and thus ended his many years of service to the Royal Household.

Retrenchment in the face of retirement meant that, with great regret, the Hampstead house would have to be sold and a smaller house ‘Little Orchards’ rented in Hertfordshire. And it was here, in the midst of orchards and pastures that John announced one morning: ‘I believe the d…..d thing’s done!’. Thirty-six years of toil, producing thirteen volumes, were over. The History of the British Army begins with Cromwell’s Standing Army of 1645 and ends in 1879. It was dedicated to Winifred: ‘And there is she, nearest of all to me who, in defiance of pain and sickness, has fought incessantly to win me the leisure for completion of my task, and by sheer courage and resolution has prevailed’.

The recompense was small. The set of volumes was expensive and, in the post-war world, did not sell as well as anticipated. The completion of the work did not, as was hoped, solve their money problems. But acclaim from historians, military academies and soldiers from all over the world was immensely gratifying. The scope of his research and wealth of documentation gained John the title ‘Historian of the British Army’ as well as the Chesney Gold Medal, given to those who had made a lifelong distinguished contribution in the fields of defence of the realm. In the years completing the History he had also written three more books, which included My Native Devon and a biography of Wellington.

But the constant money worries, coupled perhaps with the fact that they had a less than significant social life in England (partly by choice) gradually convinced them they would be better off abroad. Friends recommended the region of Grasse, for its more reasonable prices and healthy climate. In spite of the depression in America the pound was strong and bought a pleasing number of francs, so in 1930 the decision was made to search for their dream home in the sun where a comfortable, even elegant, life could be purchased for appreciably less than in England.

The house the couple found in France has passed into the history of popular literature of the 1930s and ‘40s. It, and the life around it, is described with humour and poignancy in Winifred’s best selling book Perfume From Provence, which made her famous throughout Britain and the Colonies. She would go on to write six more books on her life in England and Provence.

The Domaine Fortescue, as they called it, was a simple house near the village of Magagnosc, just below Grasse. There was much to be done in the way of restoration but John was entranced by the project and, with 124 francs to the pound: ‘We should do it easily and we can write a few articles to pay for extras’. But in 1931 Britain suddenly came off the Gold Standard and the value of sterling plummeted. The amount of francs to the pound dropped with it and, for many permanent expatriates, life became suddenly and unexpectedly worrying. For John and Winifred, with contracts signed, it was now too late to turn back. All this meant, agonisingly, that lack of funds would return to haunt them. Above all, instead of the tranquil retirement so richly deserved, John would have to sit again for long hours at his writing-desk and earn by his pen. Around him builders drilled, banged and filled the air with choking dust. But during these years, along with a flow of articles, he wrote nine more books including The Empire and the Army; The Royal Army Service Corps; Following the Drum and a biography of Marlborough. His gentle autobiography is entitled Author and Curator.

Right – The Domaine in the 1930’s when owned by John & Winifred

In spite of continual financial worries they were happy in La Domaine. When not writing, John tended his vines and fruit trees and oversaw the progress of the vegetable garden. In the restored house, his ‘Gallant Company’ decorated the salon. These were the prints of some of the soldiers to whose stories John had devoted much of his life, and which accompanied him everywhere. But in the summer of 1931 John ‘became suddenly and terrifyingly ill’. It was almost certainly a stroke, for he fell into a coma. He recovered, but the illness meant that from now on he would always be fragile. But this didn’t prevent him, in convalescence, from ‘writing, writing, writing’, so badly did they need to balance their budget.

John was able to enjoy his Provençal home for scarcely three years, for he died in the small Anglo-American Hospital in Cannes in September 1933 after an operation for appendicitis, performed too late. The simple funeral service was held in the tiny hospital chapel-room during a sunlit break after several storm-tossed days. His coffin was covered with the Union Jack and, obedient to his wishes, Winifred did not follow him to the crematorium from where his ashes were to be sent to England to be scattered on his beloved Devon moorland. Instead, once the hearse had left, she went into the garden of the little hospital and looked across the valley to the road beyond:

‘As I looked, suddenly a glorious rainbow shone forth, completely spanning it, and, under this radiant bridge, rushed a great car. I saw a flash of colour - red, white and blue........... Then the storm broke and thunder roared a last salute.’ © 'Perfume from Provence' by Lady Winifred Fortescue

© Copyright: Maureen Emerson 2019

Simonsbath in Exmoor National Park

The cairn above Simonsbath in Exmoor National Park – built in memory of Sir John Fortescue at Winifred’s suggestion

Memorial on the front of the cairn

John Fortescue’s former hunting lodge at Simonsbath, Exmoor – now a hotel