The Riviera of the 1920’s

The 1920s are considered an era of increasing affluence and consumerism. Along with peace and the growing prosperity of the Allied countries, had come better opportunities for travel and, for the British and Americans, the post-war exchange rate with the French franc was favourable. By 1925, great ocean liners were bringing an increasing number of tourists to Europe from the United States. If they came via England they could continue their journey by train – a luxurious even thrilling, experience. The Golden Arrow to Dover became The Flèche d’Or at Calais, which raced on to the Gare du Nord in Paris. From the Gare de Lyon one could board the PLM (Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée) Pullman Express or its overnight partner the Train Bleu – the first of its kind with metal carriages manufactured by the Leeds Forge Company of Birmingham in England. This first-class only train, which ran from Calais, was launched in 1922, its restaurant and wagons-lits decorated with exquisite Art Deco marquetry by K. Morisson and René Prou. The paintwork, blue with a gold trim, heralded its destination – the blue waters and golden sun of the Mediterranean. Headed for the south, the train was the inspiration for the ballet Le Train Bleu of 1924 for which Jean Cocteau wrote the text and Darius Milhaud the music, with the stage curtain painted by Pablo Picasso. Coco Chanel designed the costumes of thigh-length knitted and belted swimsuits and head-hugging bathing caps.

For those who preferred to travel by motor, the wonderful cars of the decade, the Bugatti Decapotables, Minervas, Hispano-Suizas, Lagondas and Rolls Royce Silver Ghosts, with their new combustion engines, cruised across France and bore their occupants to the delights of Cannes and Nice and along the corniche roads to Beaulieu and Monte Carlo. It was the age of the coach builder. New inventions abounded. In May 1927 Charles Lindbergh flew his Ryan monoplane between New York and Paris in the greatest solo flight in air history. Sir Frederick Banting invented insulin, Alexander Fleming penicillin and Philip Drinker the Iron Lung. Radio came into its own. Cinema, trying desperately to find a firm footing in this new world, began to move from silent pictures to talkies.

Cannes, the writer Stéphan Liégard felt, ‘can boast a sun forged especially for duchesses’. Liégard also coined the term La Côte d’Azur to complement the deep summer blue of its sea along the coastline. Curving around its wide bay, Cannes has a gentler climate than Nice, protected as it is by its amphitheatre of hills. At the western end is the old port, flanked by the Quai St Pierre and overlooked by Le Suquet, the original village perched on an outcrop of rock. During most of its history Cannes was no more than a simple fishing village. Discovery of its charms in the mid-nineteenth century by Lord Henry Brougham, an ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer of the British government, transformed it into one of the most elegant and sought-after resorts in the world. By the end of the 1880s Guy de Maupassant would write laconically of the town, ‘Des princes, des princes, partout des princes.’ In the early 1920s the small port was still filled with the wooden fishing boats and spread nets of the fishermen who frequented the bars on the quay above.

Nearby, the pretty white Municipal Casino of 1907 was the gate lodge for the palm-lined Croisette. This elegant promenade, flanked by its famous hotels, runs for around two kilometers along the shoreline. On the Croisette (which began life as the ‘Path of the Little Cross’) the Carlton Hotel, with its wedding-cake stucco-work, would serve as Barry Dierks and Eric Sawyers letter box, and the Carlton terrace, crowded to capacity at cocktail hour, replace the Ritz bar as the place to see and to be seen. At that time the hotel boasted five tennis courts which hosted competitions entered by such as the champions Suzanne Lenglen and Jean Borotra.

It was a heady time for the young, particularly young women. The war liberated them to an extent unable to be visualised before 1914. White American women finally gained the vote in 1920, with African-Americans and American Indians continuing to be marginalised. In the United Kingdom votes for all women over twenty-one would not happen until 1928. Women in France had to wait until 1944. But now, compared with their, often disapproving, mothers they were wonderfully free. They cut their hair short, hairstyles ranging from the Shingle to the Marcel-Waved Bob. The privileged drove sports cars, perched on stools in cocktail bars, smoked cigarettes in long holders and danced with abandon. Along with the cigarettes, opium, ‘le dérangement de tous les sens’ (the disruption of all the senses), was available for those who desired it. Sauciness, which always featured young women, abounded in postcards, revues and in Hollywood films.

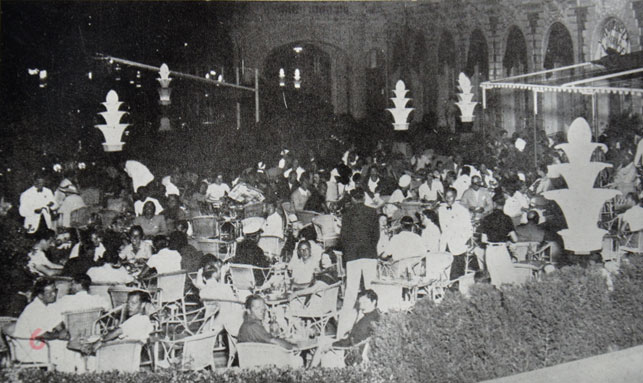

The hotels and restaurants of the coast were filled with voices of diverse nationalities. These included le gratin, the royalty and aristocracy of Europe, (the Russian contingent often impecunious), the business moguls, playboys and celebrities who chattered to the accompaniment of the clinking of ice in newly created cocktails and the tinkling of Irving Berlin or Jerome Kern tunes on a baby grand. Later in the evening there would be dinners in private houses or at fashionable restaurants. From designers such as Poiret, Molyneux or Vionnet the women chose their garçonne-look: loose drop-waisted gowns, which grew ever shorter as the decade wore on. These were worn with silver hose and, against the chill of a Riviera winter evening, cloak-coats edged with fur. For the young, and sometimes not-so-young, it was mandatory to spend the rest of the night dancing, often frenetically, in one of the newest creations of the 1920s – the nightclub – which Jean Louis de Faucigny-Lucinge in his Memoires called ‘the fever of the age’. How better if one had the means to forget, even for a moment, those lost forever?

Periodicals such as La Saison de Cannes and Le Journal des Etrangers detailed the arrival of rich visitors to the coast. These visits were an opportunity for glamour, sophisticated entertainment and the chance to meet old friends and make new ones. Enjoyment was enhanced by starlit nights beside the rippling Mediterranean and the frisson of a Latin environment. It was not for nothing the couturier Jeanne Lanvin named her perfumes, created in Grasse, My Sin, Scandale, Rumeur and Prétexte. And there was no Prohibition.

This new, younger set, La Bohème Chic, began to realise there was much pleasure to be had exercising vigorously in the sunshine or lying languorously on a beach. Although many different nationalities now returned to the coast after the war, this was the era of the Americans. During the war many thousands of young servicemen from the United States had been cared for and convalesced in the great hotels of the Riviera, requisitioned as hospitals and nursing homes – and many would return as tourists. In 1921 Cole and Linda Porter rented the Château de la Garoupe on the Cap d’Antibes. The Porters invited another American couple, Gerald and Sara Murphy, whose subsequent sojourns on the Cap have passed into Riviera history. From their Villa America on the heights overlooking the Garoupe lighthouse, the Murphys entertained and gave beach parties on the small beach at La Garoupe, playing host to the Picassos, Rudolph Valentino, the Hemingways and other such artistic luminaries. Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night was born when he and his tempestuous Zelda joined their circle, and set the astonishing trend for summers in the sun. The body beautiful became almost an obsession, the beaches along the coast playing host to exercise and dance classes. Golf, tennis, polo, swimming and sailing were pursued with great enthusiasm. The freedom of a lightly-clad tanned body, caressed by the sun, was a new and voluptuous experience, dignified by Coco Chanel, who soon acquired a glamorous tan of her own. Chanel and her lover, Bendor the 2nd Duke of Westminster.

Among the many names which feature in the history of the Riviera of that time was Isadora Duncan from San Francisco. Claimed as being the originator of modern dance, she lived spasmodically on the coast with her various lovers, giving performances and dance lessons. Dogged by tragedy, increasingly eccentric, debt-ridden and notorious for her bouts of drunkenness, in 1927 she met her end in an appropriately dramatic fashion. Driving away from her studio on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice in an Amilcar Grand Sport driven by the handsome racing driver Benoit Falchetto, her voluminous shawl flew back and caught in the spokes of the rear wheel. The shawl throttled her, she was flung onto the road and died instantly.

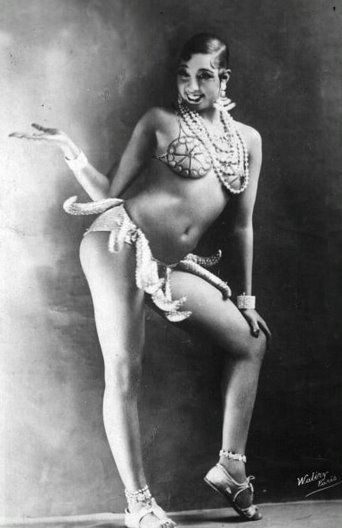

Also in 1927 Josephine Baker, the ‘Black Pearl’ from St Louis, an erotic dancer and civil rights supporter performed her ‘chocolate arabesques’, as Scott Fitzgerald described them, and her version of the Charleston in La Revue Nègre in Nice. And with the Americans came jazz – music whose influence has endured on the Riviera to the present day.

On the coast and in the back country the artists dreamed and painted. Matisse had settled in the Regina Palace apartments in Cimiez at Nice and painted the town and its interiors frequently during his ‘Nice period’ of the 1920s. In 1926 Pierre Bonnard bought the villa Le Bosquet at Le Cannet, above Cannes, his home for the rest of his life; Marc Chagall roamed the coastline painting the contrast of sea, rocks and vegetation he admired so much. It was not long since Renoir had died at his hillside farmhouse, Les Collettes, at Haut de Cagnes.

During 1925, a silent film based on the war, Mare Nostrum, was being shot at the Victorine Studios in Nice, run by the multi-talented director Rex Ingram along with a young Englishman, Michael Powell. Powell would later join Emeric Pressburger to make the acclaimed Powell-Pressburger films, such as The Red Shoes. From Antibes to Juan-les-Pins the pine woods run parallel with the sandy beaches and here, in 1925, the American millionaire Frank Jay Gould built his 254-room Art Deco Hotel Provençal. Buying into and modernising the newly successful casino Gould, along with his wife Florence, would establish the small town under its pins parasols as a young and lively summer resort. Florence would later proclaim ‘… everyone slept with everyone. It was amusing, it was practical.’ A lover of all water sports, she established the first water skiing centre at Juan les Pins, and here the first beach pyjamas were worn – to the despair of the old guard of Cannes. And in 1926 Jean Patou invented the very first sun cream – Huile de Chaldée. It was all very glamorous. The contrast between the coast, and the hills which rose behind, was never more marked than at this point in time, and there were those in the hills who did not go down to the coast during their lifetime. While, for the well-off, the towns below sparkled with electric light, running water and gleaming bathrooms, a short motor ride to a hill village would reveal lighting by paraffin lamps, cooking on small wood-fired ranges and, for many households, water fetched from the village pump. Clothes washing was still done in the communal washing trough and flush lavatories did not appear, in some cases, until the early 1960s. In what was then intensely rural, even primitive, countryside the peasants still took their animals into the lower rooms of their homes in winter, as they would for many years to come. Conditions of life were as spartan as they had been over the past few centuries.

The large, heavy villas which had sprung up along the coast since the mid-1800s were a mixture of home-grown and transplanted architecture, consisting of Belle-Epoque, neo-Baroque, Mauresque, Neo-Classic and Scots-Gothic. Of the few modernist villas from the early part of the 1920s only two really stand out. Two years before Barry Dierks arrived on the coast, the French architect Robert Mallet-Stevens had designed the Clos St Bernard (also known as the Villa Noailles) at Hyères in the Var, for Count Charles de Noailles and his wife Marie-Laure, patrons of the Surrealists. A large, severe house of grey reinforced concrete, it overlooked a splendid view of the old town. Their neighbour, who had a right of passage through the property, was the American novelist Edith Wharton who wintered in her, very different, Castel St Claire every year until her death in 1937, ‘keeping in touch with America from afar’. It was at Hyères that Wharton wrote The Age of Innocence, which won her the Pulitzer prize, making her the first woman recipient.

In 1925 the Anglo-Irish designer Eileen Gray created at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin near Monaco what was perhaps the most evocative of early modernist villas on the coast – the ill-fated ‘E1027’. Gray, who did much work with Le Corbusier, built her iconic house on a terrace of rocks above the sea. Intended as a summer home, she designed the villa in collaboration with her lover, the Romanian architect Jean Badovici, creator of the journal Architecture Vivante. The obscure house name of a letter and numbers was a code, E for Eileen, then a set of numbers relating to their names, out of sequence so intertwined like the lovers they were at this time. The stunning design, finished in 1927 had, like the Villa Noailles, the shape of an ocean liner. This, a pure example of the architect Le Corbusier’s ‘new beauty’, although not designed by him, caused the latter to become consumed by jealousy. At the end of the 1930s, Eileen Gray being absent, he would enter the house and deface the interior with sexually-charged murals, much to Gray’s chagrin. In 1932, Gray designed and built another home for herself alone. On a plot near the village of Castallar high above Menton and adjoining an old farmhouse it was, like her Roquebrune house, simple, modern, space-saving and light-embracing. She called it Temp à Pailla. In 1956 she would sell it to the British artist Graham Sutherland.

The great hotels or palaces of the Riviera stood proudly, as they do today, the Carlton on the Croisette in Cannes designed by Charles Delmas in 1911 and Edouard Nierman’s Negresco on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice in 1912. The Hôtel Hermitage in Monte Carlo graced the municipality as early as the 1890s, designed by Nicolas Marquet with a lobby designed by Gustave Eiffel. These grand buildings were resplendent with their embellishments, domes and turrets, as was the Monte Carlo Casino of 1893, built by Charles Garnier, the architect of the Paris Opera. They were the admired edifices of the coast, favoured by those who could afford their luxury. The Riviera did not embrace the new movement in architecture as eagerly as some of the cities and large towns of Europe, but the post-war years of the 1920s began to produce a few trail blazers. On the Croisette at Cannes, Charles Nicod and Emile Molinié designed the Art Deco Hotel Majestic, the main part of which opened in 1926. However, it was not until the later part of the decade that a new brand of hoteliers would adopt the modernist style with enthusiasm. In 1932 Georges-Henri Pingusson built his startlingly modern Hôtel Latitude 43 his barre de béton blanc (bar of white concrete) at far away Saint Tropez.

The elegant villas of the coast now had to be equipped for entertaining. The constant ebb and flow of socialising from house to house was a way of life that only came to an end with World War Two. It was all, once more, as Edward VII had observed, ‘like a constant garden party’.

© Copyright: Maureen Emerson 2021