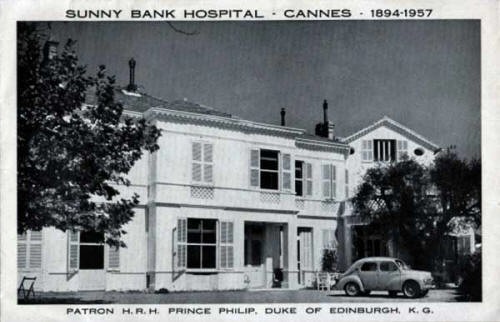

Sunny Bank Hospital

Be ill in your own language!

“We congratulate ourselves on each new link that unites England and France”

Sir Sydney Waterlow – 1897

One April day in 1897 the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, together with his entourage, was driven up the Boulevard Carnot in Cannes, his cortège eventually joining a narrow lane that climbed one of the hills behind the town. Awaiting him before a low white villa were the great and good of the expatriate community. The Memorial Foundation stone of the newly enlarged English Hospital at the Villa Sunny Bank was about to be laid. The entrance was decorated with English and French flags: ‘Dont les couleurs se marientfraternellement’.

Among those watching the Prince tap the stone into place were the gratin of Cannes, including Lord Brougham and Vaux whose father, a past Lord Chancellor of Great Britain, had in the 1830s made the decision to build a villa in this small, unknown fishing village, thus changing its destiny for ever. Here Brougham had drawn around him the aristocrats and rich of first Britain and then virtually the rest of the world. Reading the welcoming speech on that April day was Sir Sydney Waterlow, ex-Lord Mayor of London (who, with his American wife, entertained the crowned heads of Europe in their Villa Monterey). Twenty-four of those present had titles, including a small sprinkling of French aristocrats, and some would eventually be laid to rest in tombs in the English cemetery at the Grand Jasto the north-west of the town.

No account of expatriate life on the Riviera would be complete without mentioning Sunny Bank. Established in 1892: ‘For the treatment of grave medical and surgical cases of illness occurring in the families of residents for the Season, and visitors to the hotels’, the English Hospital was initially open only during the months of January to May, when the doors were then closed for the rest of the year. In spite of the increasing popularity of the Cote d’Azur as a summer playground in the 1930s, it only then extended its working period from September to May, although, in many cases, nurses stayed on to do private nursing in their patients’ homes. As late as the 1940s Winifred, Lady Fortescue, author of Perfume from Provence a best-selling book of the period, was advising a friend who was expecting a visitor in frail health, that: ‘She simply can’t be ill in summer as Sunny Bank doesn’t open until September.’

Gathering the addendum ‘Anglo-American’ along the way, the hospital remained very British. Receiving no government funds of any kind meant that financing was a constant problem. Operating on a policy of patients paying according to their means, with no one being refused entry for lack of money, the small hospital was always heavily reliant on the generosity of expatriate and French residents and visitors to the Riviera, plus income from various fund-raising events. Expanding in 1925 and again in 1932enlargement was crowned, in 1970, by the gift of a wing of four rooms by Nubar Gulbenkian, ‘Mr Five per Cent’, one of the world’s richest men, whose fortune was made in Iranian oil and who died in the hospital in 1972. By that time sixteen patients could be accommodated in single rooms. Always staffed by a Matron of the old school and her British-trained, crisp-uniformed nurses, along with help from local French personnel, it was to Sunny Bank, up until the 1990s, that the English-speaking expatriates of the area fled if they were anxious and needed to be ill in their own language. French patients (particularly those who had married English citizens) were welcomed, the only criteria being that they spoke English.

At the outbreak of the First World War the Committee of the hospital had offered its services to various organisations needing facilities to care for the wounded. These suggestions were politely refused and it continued to operate as a civilian hospital. Similar offers were made in 1940 – and similarly refused. But the south of France would be a very different place in this war and Sunny Bank was affected accordingly.

The difficult years at the beginning of the Second World War had become even more so when Nazi troops, after Italy signed an armistice with the Allies, took over the south of France completely in Autumn of 1943. The English church in the town was closed and the English library ransacked, some disapproved-of books being burnt others, if they were of value, sent to Germany . The staff at Sunny Bank was headed by the Matron, Margaret Williams and her second-in-command Nurse Gladman. The doctor on call was the respected Dr Ginner. They were under strict instruction to present themselves regularly at the Mairie in order to have their fingerprints taken. Plain clothes agents visited the hospital to search for people in hiding and all patients had to be checked and signed for. At first British citizens were confined to the town limits and later, as an Allied invasion threatened, ordered to go beyond 100 kilometres of the coast. Others, more suspect, were sent to a concentration camp at Grenoble and these included Dr. Ginner, leaving the hospital in the care of a French doctor, who took a great risk in being involved with the British. Although increasingly under threat of evacuation to the hinterland, the nurses and patients were always reprieved.

During the years of war, a hidden radio in the basement kept the staff abreast of events in the world outside. There is a story that a German officer, arriving unannounced for an inspection, entered the basement, gazed at the radio and then withdrew, saying he had seen nothing out of the ordinary. So it was with both hope and fear that in August of 1944 the nurses spread a great Red Cross flag over thecourtyard in front of the hospital as Allied bombers thundered over Cannes in order to knock out the gun emplacements on the, so very near, hills above.

After Victory in Europe day in 1945, Miss Williams and Nurse Gladman closed up a, now empty, Sunny Bank and returned to England for the rest of the year. It was re-opened again in 1946.Nurse Gladman soon left to become Matron of the newly refurbished Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital in Nice, which had suffered badly during the war. She nursed there for seventeen years and received the M.B.E. on her retirement. Margaret Williams continued as Matron of Sunny Bank until her own retirement in 1955. For over forty years after that a small framed certificate hung on a pillar in the small hallway of the hospital. King George VI had written: ‘I greatly regret that I am unable to give you personally the award which you have so well earned.’ This was the O.B.E. She too, had played her part.

In its last years the hospital continued to care for members of the British and American communities. But, as time went on, the changes in the nature of the community on the Riviera, coupled with the National Health Service in an ever more accessible England, plus the rapidly increasing efficiency and ultra-modern facilities of the French hospitals, saw the Sunny Bank Anglo-American Hospital draw slowly to the end of its era. Shortly after celebrating its 100th anniversary on 8 April 1997, it was razed to the ground. Here, in place of the building whose first nurses welcomed patients descending from horse-drawn carriages, which had stayed open through two world wars and cared for such as Winston Churchill and Somerset Maugham, stands a small, modern block of flats. But a new Sunny Bank is well on the way to a sort of resurrection. On land bought at the village of Mouans-Sartoux, somewhat higher and to the west, a state-of-the-art retirement home will be built, created in the spirit of the hospital, even if not able to keep its name. Many people look forward to its completion with the same feeling of confidence the little hospital inspired over its long history.

© Copyright: Maureen Emerson 2009