The Story of Hélène Vagliano

Légion d’Honneur, Chevalière; Croix de Guerre avec Palme; Medaille de la Résistance

Large dark eyes look out, under arched brows, from an oval face. The look is serious, but the subject of the photograph could not have known what life held in store for her. She is Hélène Vagliano and her story should not be forgotten. Hélène’s parents were part of a large and respected Franco-Greek background of bankers and merchant ship owners with strong links to England. There is a Vagliano tomb in West Norwood cemetery in London. Hélène was born in Paris in 1909 but the family, her father Marino, her mother Danaë, Hélène and her two brothers, moved to England, living at The Grange at Ascot near Windsor, where they had one of their elegant houses and admired gardens. Much later, in very different circumstances, Danaë Vagliano would remember these gardens and the lake ‘on which floated swans, as white as snow’.

Left – Hélène Vagliano, Légion d’Honneur, Chevalier; Croix de Guerre avec Palme; Medaille de la Résistance

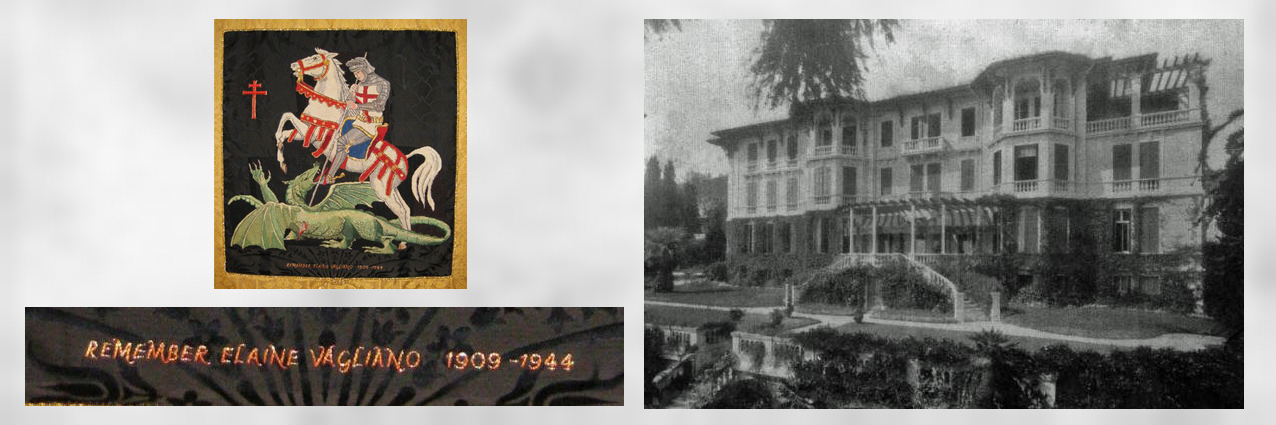

In 1924 Hélène’s parents moved to Cannes, in the south of France, and Hélène (always Elaine to her English friends) became a boarder at St. George’s School in Ascot. At this private all-girls school, she was successful and popular. Her serious expression in her photograph belies her high spirits and mischievous sense of humour. She was a model pupil, a prefect, a promising pianist and played goal in the 1st lacrosse team. She spoke French fluently but, as the result of her schooling, would always speak it with a pronounced English accent. A fact which would count against her in the future.

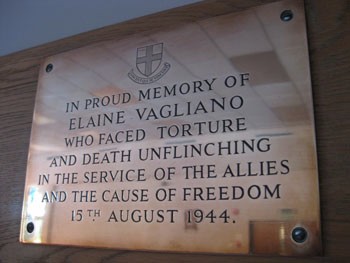

Once in Cannes the Vaglianos bought land in the Californie district and here they built the impressive Villa Champfleuri, where Danaë created a garden of such importance it is now under a preservation order. Here there were flamingos on the small lakes, rather than swans.

In 1927 Hélène left her school in Ascot and joined her family in Cannes, where her parents had already settled comfortably into expatriate life. Hélène’s father, Marino, was a champion golfer and President of the prestigious Golf Club at Cannes-La Napoule (during the German occupation in the last months of the second world war, this golf course would be planted with around 2,000 land mines). Danaë became captain of the French Ladies’ Golf Team, and the international Vagliano Trophy still exists in her name. From here, living the life of a typical, privileged, young Riviera girl of the 1930s, Hélène regularly sent news of her escapades to the Alumni magazine of her old school in England. She bought herself a speed-boat ‘it’s tremendously thrilling, especially turning corners’, skied and mountaineered with her brother which ‘gave the guide many white hairs’. She trained tortoises ‘one gets almost breathless chasing them’ and generally enjoyed herself thoroughly. In the midst of this gaiety she also translated articles into Braille for periodicals for the blind and became involved in the activities of the British community in Cannes, becoming Brown Owl of the 1st Cannes Pack of Brownies. She was also a Scout Leader with the Cannes Scout Group and is the only woman to be recorded in The Scout Association’s Second World War Roll of Honour.

All this would change with the declaration of war in September 1939, followed by the dreary months of the Phoney War or Drôle de Guerre. The expatriate community along the coast, particularly in Cannes, sprang into action. Numerous aid programmes were launched and their letter headings sport the names of many of the great and good of the Riviera at that time. Hélène and her mother joined the committee of the Military Canteen at Cannes station, set up to provide refreshments for the troops being sent to defend the frontier with Italy. But, several months later, as the German army breached the border from Belgium and swept across France, the vast majority of these expatriates fled the Riviera. By July 1940 France had capitulated, making a prisoner of war of one of Hélène’s brothers, and the south had fallen under the yoke of the Vichy government. Firmly anti-Nazi and anti-Vichy, the Vaglianos stayed, wisely keeping a low profile.

Right – St. George’s School, Ascot

By 1941 Hélène had become the local organiser for the Social Services Department of the Maison du Prisonnier in Cannes – a prisoners’ aid organisation which cared for the families and orphans of lost and imprisoned soldiers. As the war progressed, and virtually everyone became permanently hungry, Hélène would, each week, take groups of the children to restaurants where they could have a rare good meal. She was recognised as being as generous with her money as with her compassion and known never to doubt the final victory of the Allies.

In 1943 the oppression in the south increased as the Allies swarmed into North Africa, Italy capitulated and the German Army occupied totally the ‘Free’ Zone of Vichy France. For Hélène aid work was now not enough and, unknown to her parents, she joined the Resistance. All her physical and intellectual energy had now found a cause. Although her mother would say later ‘she worked with the English’, Hélène is not on the list of agents of the Special Operations Executive. However, she seems to have been involved with more than one scheme to help the Allies. As well as working with a local Resistance group or reseau, which helped the hunted to escape from France through Spain, she became an agent for the Bureau Central de Renseignments et Action (BCRA) operating out of London. This was an organisation created, at the request of Winston Churchill, by De Gaulle’s Free French government-in-exile, to inform the Allies of enemy movements and prepare for liberation. Hélène’s group, led by Dr Paul Schmierer, was Tartane-Massena working on the Riviera, and in it her code name was Veilleuse. She also became a ‘letter box’ for the Allies and, equipped with a radio, sent and received messages and kept her control informed on the activities of the German Army, for by now the Gris-Verts (called after the colour of their uniform) were anticipating an invasion along the coast. The slightly built Hélène was frequently to be seen on her bicycle in and around Cannes, with messages hidden in the handlebars and sometimes, rather recklessly, her radio camouflaged in the rear basket.

On 28 July 1944, at a time when hope was beginning to grow into certainty for an Allied invasion, a car drew up outside the building where Hélène worked. In it were a group of Frenchmen, members of Jacques Doriot’s Legion des Volontaires Français Contre le Bolchévisme headed, as was usual, by a German officer. This organisation, virulently anti-Communist and arch-collaborators, frequently worked cheek by jowl with the local French Milice. The latter group, operating virtually outside the law, was composed of Frenchmen dedicated to hunting members of the Resistance. Denounced by an arrested woman, whose son she had helped to escape, Hélène was taken away. Later on the same day, at the Villa Champfleury, her parents were roughly arrested as hostages, in a move designed to pressure Hélène into betraying her fellow Resistants.

The torture of Hélène began immediately at the Villa Montfleury, the notorious Gestapo headquarters of Cannes. Over the next seventeen days, in different places, it continued. In prison in Grasse, in the Villa Trianon at Cimiez in Nice and then in a military prison in the same town, her parents always being moved near to her in the same building to ensure they were kept aware of her suffering. Prisoners were kept in badly-lit, verminous cells where often there was no water to wash in or to drink. Hélène was burnt on her body with a laundry iron and repeatedly kicked and beaten, her only reply being always: ‘Je ne sais pas’. This regime continued until the day when, unable to bear the terrible conditions her parents were suffering and in order to free them, Hélène signed a confession full of invented names and addresses. As her mother was being released she had time to tell her that she would: ‘Send them all over France, looking for people who don’t exist’.

On the 15 August, from her cell, Hélène heard a voice calling out in the street that the Allies had landed along the coast at Frejus. Overjoyed, she exclaimed to her cell companion, who later relayed it to Hélène’s mother, that now France was liberated nothing else mattered and her work was done: ‘mon petit morceau est fini’. During the course of the same afternoon, on a Riviera bombarded day and night by Allied planes, Hélène and twenty-three other prisoners were collected together and driven in the direction of the Ariane quarter behind Nice. The road to their destination was called the Chemin de la Croix – the Path of the Cross. On a piece of land in front of a sheer rock face and bordered by a small river, the group was lined up to face the water. Watched with horror from behind closed shutters by a local farmer and his daughter, the Germans set up their machine guns across the river from the prisoners. All twenty-four died that day. On Hélène’s right fell a priest who had been arrested for burying two Resistants shot by the Gestapo. On her left, a young blonde girl who had acted as nurse to the Maquis. Further down was Commandant de Lattre de Tassigny, a retired cousin of the General de Lattre who would lead the French forces from the beaches of the Riviera to victory in Berlin. The Commander’s son had joined the Resistance and his father had been taken as hostage. The son had already been captured and shot two days previously. Lying beside Hélène was a little basket, which her mother had managed to get to her, containing a piece of bread and a pear. It was her lunch, for she had thought she was being taken to another prison to be interrogated.

Six weeks after her death, her body was brought back to the Town Hall in a liberated Cannes, where a street would later bear her name. The coffin, covered by the French Flag, the Tricolore, was laid on a gun-carriage draped in white. All night long a guard of honour of men and women of the Resistance watched over her. The crowds at the funeral at the Russian Orthodox church the following day were enormous, every Resistance group in the south was represented, the men marching with their guns reversed. A singer sang Avé Maria, for Hélène had died on the Day of the Assumption, and this was followed by her favourite piece by Bach, Viens Douce Mort. She now lies in the crypt of the church where, each year on the anniversary of her death, a service is held in her memory.

Sources: Hôtes de la Gestapo by Danaë Vagliano, Archives of Cannes, France, Musée de la Resistance, Nice, France, The Dragon. The Alumni Magazine of St. George’s School, Ascot, The archives of Girl-guiding UK & Scout Association.

© Copyright: Maureen Emerson 2011