From Occupation to Liberation

Claude Marcus’s Story

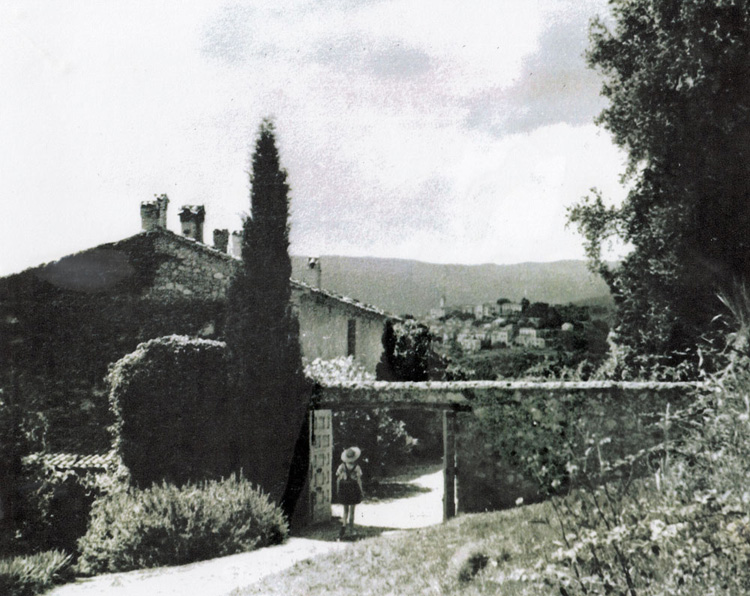

A hill, then called the Colline des Anglais by the local people (now the Chemin du Château) stands high in the hills above Antibes, and is a shady country lane bordered by four charming old houses of various sizes, Le Castello, San Peyre, La Bastide and Fort Fortescue. Between the two world wars, the four houses were owned by four expatriates, one American woman, two English women and one English Marquess, all friends. By 1940 three of these had fled back to England, only the American, Elisabeth Parrish Starr, a heroine of the 1st World War, stayed on in order to join a small local Resistance group formed to shelter Jewish families fleeing persecution. Elisabeth Starr’s own work ended with her death in 1943 from illness and malnutrition. She was 54.

But others continued to hide vulnerable people, even when it became extremely dangerous to do so. Two communist schoolteachers, Monsieur and Madame Dardaillon, who taught in the nearby village of Le Rouret, gave lessons to Jewish children hidden in the Castello. This couple also brought to a fine art the act of entering the local Mairie at night, under pretext of using the telephone, to stamp false papers, les faux papiers, in order to help people escape deportation.

Since November 1942 the south-east of the unoccupied zone had been more or less settled under Italian military rule. This meant that, after the terrifying roundups of non-French Jews in July and August of 1942, Jewish refugees (especially of French nationality) now felt more secure. The Italians had little tradition of anti-Semitism and for this reason, and because they resented being dictated to by the Germans, they contrived to block the Nazi–Vichy effort to deport Jews to a, then, unknown fate. For the fact this minefield was negotiated with skill by his ministers, Mussolini must be given credit.

Dr Suzanne Perles, a Jewish doctor practising in Cannes and protected by her French employer, learnt about the vacant houses on the hill, and arranged to rent the Bastide. Here the family felt safer, away from the coast. The household comprised of Dr Perles, her husband, who was also treasurer to a group of local Resistants, and their three children, Alain, Nicole, a younger son, plus several friends. One of these friends was a young man named Claude Marcus, although, by sleight of hand, he had sensibly changed the name on his identity card from ‘Marcus’ to ‘Marais’. His age was entered as seventeen, although he was nineteen, for this enabled him to escape the Travaux Forcé, the Forced Labour decree that sent young men to work in the fields and factories of Germany. Claude’s parents had sent him up to Opio from their apartment in Le Cannet, on the hill behind Cannes, for in spite of the relative benevolence of the Italians they felt he would be safer away from the town.

The summer progressed through its simmering heat. Bicycle rides were taken with no hindrance, around the neighbouring countryside and to and from the coast. The cicadas sang and grapes (soon to be picked and almost all requisitioned) ripened on their gnarled stumps. Food became ever scarcer. A great fig tree grew in the front garden of the Bastide, and figs could quickly be eaten before the ‘Inspectors’ spotted them.

Charles Anglesey’s San Peyre was also let. The Bogobzas were from Marseille, an unsafe place from any angle. Monsieur Bogobza was Jewish and his wife Catholic. Of their children, the youngest had suffered from polio and was partially paralysed. Mr Bogobza was remembered for his gentleness and, each time he fetched the bread from the boulangerie, for giving sweets to any loitering village children.

During these months the two families would visit an elderly woman, Diane van Dommerlen, at the Castello for lunch or dinner, pooling their meagre rations. Diane had cared for Elisabeth Starr during her last weeks and now, without foundation, felt she was the new chîatelaine of the large country house. Although later it would be hard to know whether Diane was rather good or really rather bad now, at personal risk, she was supportive and brave towards the Jewish families on the hill.

In July of 1943, the month that Claude Marcus joined the Perles at Opio, American forces captured Palermo in Sicily. Mussolini was suddenly arrested and Marshal Pietro Badoglio, known for his cruelty during the Italian occupation of Ethiopia and Libya, took over. Badoglio pronounced his intention to carry on with the war, but at the same time beginning negotiations with the Allies. This dithering policy boded ill for Italy and the Italians. In September, Mussolini was rescued by the Germans and re-established a fascist government at Lake Garda in northern Italy, thereby creating ‘two Italys’. On 1 October the Allies entered Naples in the south and on the 13th the Badoglio government declared that Italy was at war with Germany. In the south of France there was a mass rush eastwards towards the border by retreating Italian troops, jettisoning their arms, munitions and uniforms en route, and pursued by the Germans who had moved swiftly down and through the south. The Vichy regime became virtually impotent and the Nazis took control of the whole of France.

Now the hills of Opio had other visitors – solitary Italian soldiers, either deserters or separated from their units, trying to reach the Italian border. The families in the houses on the Colline des Anglais gave these hunted men what little food they could spare. And the Gestapo now had open season.

A brutal awakening disturbed the peace in the early morning of 23 December 1943. One of the sons of the Bogobza family at San Peyre, having rushed across the terraces, warned the Perles at the Bastide that the dreaded black Citröens had swept up to San Peyre and the Gestapo were arresting everyone at the house. The rest of the Bogobza family had tried to hide in a deep cupboard carved out of the wall beside the fireplace in the large salon, but were quickly discovered. Flung into a waiting van, they were driven off to their fate. Only the son who had warned the Perles would escape and manage to survive the war. On hearing the news, the Perles group at the Bastide rushed ‘comme des fous’out into the countryside and into hiding. The following morning they telephoned Diane at the Castello, who confirmed all was now quiet. This enabled them to return to the Bastide for the last time to collect their most vital belongings before moving back to Cannes. Opio was no longer the place to be.

Claude’s parents, still living in their apartment in Le Cannet, now decided to move to Pau on the edge of the Pyrenees, which they felt could only be safer. Meanwhile, Alain and Nicole Perles and Claude Marcus, lying low with the rest of the Perles family in Cannes, made a decision: they must cross the mountains into Spain and somehow get to North Africa and join the Fighting French. Preparations for the journey took all of January 1944. Organisers and guides had to be trustworthy. The expenses were great and the whole expedition would be in the lap of the gods. Eventually a rendezvous, in Lourdes, was arranged with a contact and the three set off separately to meet in Pau. During Claude’s journey a strange incident occurred. Nearing Toulouse a man entered his train compartment and, after a moment, began to whistle a new Irving Berlin song, familiar to Claude and only heard on the BBC, ‘This is the Army, Mr Jones’. Although bewildered, Claude was very careful not to react. Even a casual tune could open the path to the interrogation room and deportation.

Once reunited in Pau with Claude’s parents, the three friends then travelled to Lourdes to meet their contact, a craggy-faced Basque, who would arrange for them to be taken over the mountains to Spain. He told them what to take for their journey – this being the bare minimum with, above all, warm clothing, for they were to walk long hours at night and sleep in barns during the day. As part of the transaction they were instructed to leave half a five-franc note with Claude’s parents before their departure, the other half to be given to their guide once they were safely in Spain. This would, hopefully, be brought back to France to complete the note and prove all was well. They had no choice but to trust him.

On the day before their departure the three returned to Pau to take leave of Claude’s parents and gather their belongings together. Now, tense with anxiety, they decided to spend their last afternoon in a cinema. Claude would never forgive himself for those two lost hours away from his family. That evening they travelled by bus to Navarrenx, about 50 kilometres west of Pau. The escapees were seven in all, Claude, Alain and Nicole plus four others, three men and a distinguished blonde woman who introduced herself as the Comtesse de Moussac. Their guides were a father and son, and the first stage would be to cross the 30 kilometres of the forbidden zone before reaching the frontier. Anyone discovered there who was not a resident was either arrested or simply shot. The first night consisted of plodding across endless fields, clambering through hedges and barbed-wire barriers, avoiding the villages that housed German units and barking dogs. After a day spent sleeping in a barn they set off once more and were almost immediately stopped by the forward guide, who had spotted a German patrol on the small country road they were taking. Ordered to flatten themselves at the bottom of a ditch, two very long hours were spent stretched out in the cold and damp. At one point Alain leant over and whispered hoarsely in Claude’s ear, ‘Heaven is where one can cough.’

On the third night they began climbing steeply – and at the same time it began to snow heavily, for this was February in the Pyrenees. Unable to continue, they spent a freezing night in a huntsman’s cabin in front of a meagre fire, all seven, friends and strangers, huddled together for warmth. On the following morning things began to improve, for they could now walk in daylight. A long hard climb took them eventually to the top of the pass of Larrau, where they were told they now had ‘one foot in Paradise’. Then came the descent into Spain. For twelve increasingly exhausting hours they scrambled down, following a rushing mountain stream, until they came to the farm where the guide’s responsibility ended. All in all, their journey had been charmed, no injuries, no shots fired and no border guards hiding in the bushes ready to arrest them. The guide was handed the other half of the five-franc note and they were on their own. Spain had a strange relationship with the Allies. Supposedly neutral but overshadowed by Franco’s strong Nazi sympathies, it nevertheless traded its general laxity towards fugitives against insurance for the future and Allied provisions. But the system was unpredictable and anything was possible. After resting, the small group continued to trudge through the snow towards the frontier village of Orbaiceta, deciding en route that there was no point in trying to avoid any kind of Spanish control. This was fortunate, as on entering the village they immediately ran into two carabinieri in their black winged hats. Taken to a police post, their papers were checked in a relatively friendly fashion. Here the Countess observed, ‘To think that you considered avoiding them, when they’re so handsome.’

That night was spent in a guarded villa and from there they went to Pamplona, where they ate in a restaurant, rather surrealistically surrounded by captured American airmen. From there they were taken to the open prison village of Leiza in Navarro where they were told to rest, in order to recover their strength before internment. Internment began in Urberuaga – a real prison camp, surrounded by watchtowers and barbed wire, where the regime was strict and the food scarce and bad. After a spell here it was on to Molinar de Caranza, between Bilbao and Santander, and it was there that Nicole was separated from the two men and sent to a women’s camp. But the Spanish were playing their cards carefully, relaxing rules as the war swung ever more in favour of the Allies, now poised for action across the Mediterranean. Everyone in the camps was waiting for the next convoy that would take the lucky ones to Algeciras, on to Gibraltar and freedom. So it was a very good moment when Claude and Alain were told they could travel to Madrid to join the next group leaving Spain, and go there alone as long as they promised to behave themselves and not escape.

In the space of twenty-four hours they changed from prisoners to tourists. Embassies and consulates in Madrid were hives of activity. The offices of the Free French, although less luxurious than the Vichy Consulate, was far more animated. Here Claude and Alain went each week for pocket money, news of the war and, as always and everywhere, the ration of cigarettes. As ‘clandestine expatriates’ their papers had to be stamped regularly by the Spanish authorities. Nicole, released from her women’s camp, had now joined them, so all three were together once more when the long-awaited day came.

Forbidden by the British to embark for North Africa from Gibraltar, on 1 May the group took a train to Algeciras, from where launches ferried them to the Ville d’Oran, an aging ferry anchored off Gibraltar and now crewed by the Free French Navy. Along with about 100 other escapees from France and 800 British soldiers and officers, they were now on an Allied troopship, crossing a Mediterranean where German submarines patrolled and attacked constantly. In spite of these hazards, by the end of the war around 20,000 had escaped from France and made their way through Spain to join the Free French in North Africa.

Docking at the bustling port of Oran, the trio were fascinated by the sight of tiny, roofless cars scuttling around like so many ants – they had seen their first jeeps. Once in Algiers, Claude and Nicole began training as interpreters for the United States military while Alain, to his joy, was accepted as a student pilot for training in the States. The 12th Tactical Air Command of the US Air Force included four Free French squadrons. And it was as an interpreter that several months later Claude found himself flying in a Dakota, as a member of the invasion force, and not without emotion, across the bay of a still-occupied Cannes. Landing near St Tropez, soldiers and airmen went rapidly to La Foux near Ramatuelle, where a holding camp had been set up under the pine trees. Apart from one other soldier, Claude was the only Frenchman. Here he discovered another American marvel – washing up liquid.

While aircraft strafed the retreating Germans relentlessly as they fled towards the north, ground troops fought their way along the coast, through Fréjus and Agay and onwards towards Cannes. Claude, anxious to get news of those members of his family who had stayed on the Riviera, was now given permission to travel eastwards under his own steam. It was on 25 August, six months after beginning the trek to freedom, that Claude entered Cannes, newly liberated by the Americans. The victor’s return was muted. Having no transport, he borrowed a well-used woman’s bicycle and began the long climb towards Le Cannet. Pedalling along the Boulevard d’Italie, he passed another cyclist who he recognised immediately. Dr Perles was on her way down to Cannes and was astonished and thrilled to see Claude and have news of her own children, Alain and Nicole. Suzanne Perles and her youngest son had been hidden in the Convent of the Bon Pasteur in Cannes and her husband had also survived the occupation of the south. There was much news to exchange, but there was one answer she could hardly bear to give Claude, his parents had been taken at Pau in May. He would not see them again.

Claude has always said that, in spite of the events through which he lived there, he has fond memories of the charm and tranquillity of Opio, the rue de la Fontaine and its houses. He remembered the beauty of the surrounding countryside and, above all, the generous fig tree in the garden of the Bastide.

© Copyright: Maureen Emerson 2021